Contact our boss directly.

Don’t wait — our boss replies within 20 minutes to all inquiries.

Submit your question now and get professional feedback, accurate pricing, and technical advice — fast.

Key Takeaways

- PE sintered filters are tough—they handle vibration, bumps, and daily “operator reality” better than most people expect.

- Their stable pore structure delivers predictable filtration performance when you spec micron rating + thickness + porosity correctly.

- In many water-like and mildly chemical streams, PE offers a sweet spot of flow rate vs pressure drop (ΔP).

- They’re often more cost-efficient over the whole lifecycle (not just unit price) because they can run longer and get cleaned in the right applications.

- The real win is design flexibility: custom shapes, rigid bodies, and easy OEM integration without fragile media layers.

If you’re using PE sintered filters in an industrial filtration system, you’re probably not doing it to impress anyone at a trade show. You’re doing it because you want the filter to work, keep working, and not turn your maintenance team into unpaid therapists.

And honestly? I respect that.

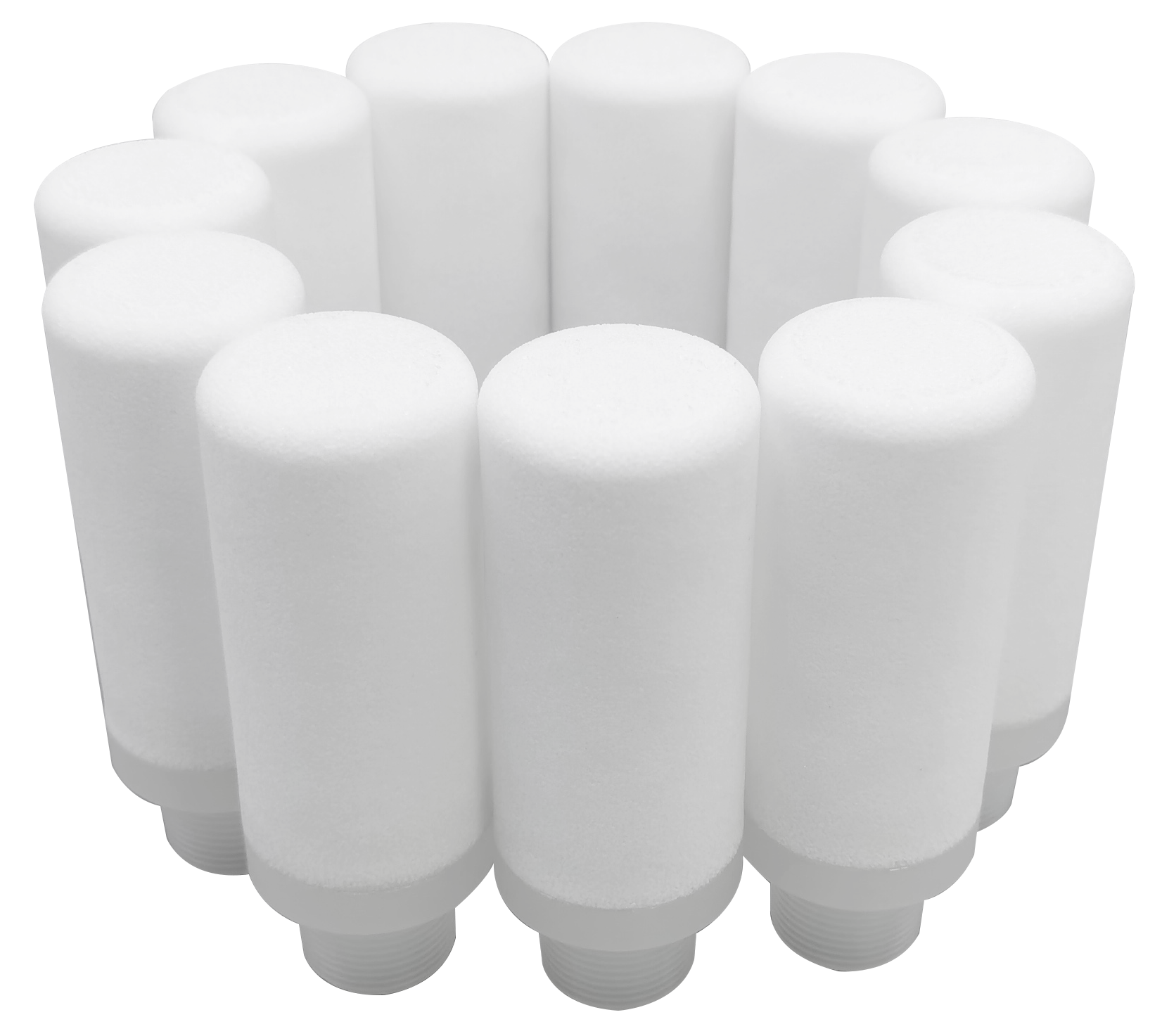

PE (polyethylene) sintered filters are the quiet “steel-toe boot” of porous plastics: not glamorous, not exotic, but stubbornly reliable in the kinds of real-world conditions that don’t show up in glossy spec sheets—pulsing flow, inconsistent solids loading, operators who tighten things “until it feels right,” and systems that run longer than anyone wants to admit.

Let’s talk about why PE sintered filtration earns its place, where it’s a bad idea, and how to spec it so it doesn’t betray you at 2 a.m.

A PE sintered filter is made by sintering polyethylene powder—heating it until particles fuse at their contact points without fully melting into a solid brick. What you get is a rigid, porous structure with interconnected pathways.

That’s fundamentally different from:

Sintered PE is like a city of tunnels. Particles don’t just hit a wall; they navigate a maze and get captured in the structure. That’s why, in the right job, it runs longer before ΔP spikes.

I’ve seen filtration decisions made in conference rooms by people who never touch the equipment. Then the filter arrives in production and gets handled like a wrench.

PE sintered filters are mechanically forgiving. They tolerate:

If your plant is spotless and everyone uses torque wrenches, congratulations—you live in a corporate slide deck. For the rest of us, toughness matters.

PE sintered filters can deliver repeatable filtration performance because the pore network is built into the body, not layered on top like a fragile cake.

But I’m going to say something unpopular: “Micron rating” alone is not a spec. It’s a hint. A clue. A starting point.

If you want predictable performance, you need to think like the filter:

Two “10 micron” filters can behave like strangers at a party.

In many industrial filtration systems—cooling water, process water, rinses, mild aqueous solutions—PE sintered filters often hit a nice equilibrium:

If your fluid is closer to “water with attitude” than “solvent from hell,” PE can be a very rational choice.

Can PE sintered filters be cleaned and reused? Often, yes. Will it work in your system? That depends on what you’re filtering.

PE filters can sometimes be cleaned using:

But here’s the trap: if your contaminant is oily, sticky, gelatinous, or polymerizing, cleaning may just turn into “redistributing the gunk artistically.”

This is where PE quietly wins big.

Sintered PE can be made into:

If you’re an OEM building a filtration module, design flexibility isn’t “nice to have.” It’s the whole game.

If your chemistry is mild and your concern is solids, PE can be a workhorse.

PE has limits. If your system runs hot and your ΔP climbs, PE can soften or creep depending on design. That’s not a moral failing; it’s physics.

If your chemical compatibility situation is “complicated,” PE might not be your safest bet. In those cases, PP or PTFE usually enter the chat.

If you need near-sterile performance, tight absolute retention, or regulatory-driven validation, you may want different media types—or a different polymer with more established validation pathways for that exact use.

Tell your supplier (or your future self) these things:

If you can’t answer half of these, don’t panic—just realize you’re still in the “discovery phase,” not the “final spec” phase.

A filter isn’t a standalone product. It’s a restriction in a loop.

Ask:

Filtration failures are often system failures wearing a filter’s name tag.

Yes—often excellent. They’re durable, stable, and can offer a strong flow/ΔP balance in water-like streams, especially where solids are present and maintenance cycles matter.

The big ones are mechanical toughness, stable pore structure, depth filtration behavior, OEM design flexibility, and often good lifecycle cost in suitable applications.

Often, yes—if the captured solids are removable and the cleaning method is compatible. Backwashing and ultrasonic cleaning can work in some cases. If contaminants are oily or sticky, reuse may be limited.

Start with the particle sizes you need to remove, then validate with flow and ΔP targets. Micron rating alone is not enough—porosity, thickness, and dirt-holding capacity matter a lot.

They’re resistant in many mild applications, especially aqueous and non-aggressive environments. For harsh chemicals, solvents, or oxidizers, you should verify compatibility carefully and consider PP or PTFE.

PE sintered filters are the kind of component that wins not by being “the best,” but by being the least dramatic. They’re tough, consistent, customizable, and—when matched to the right chemistry and temperature—annoyingly dependable.

If you want a filter that survives real industrial life (not just lab conditions), PE deserves a serious look.

Now, if you paste your Internal Links JSON, I’ll weave in 5–8 exact keyword links cleanly, and I can also tailor the article to your biggest buyer segments (water treatment, chemical processing, OEM equipment, etc.) so it pulls qualified leads instead of random clicks.